Any time you’re crossing the border and have to go through Customs, you may be in for a rude awakening. You may not know that you’re on a “Lookout” list of people, requiring agents to search your belongings at border checkpoints. It may not matter either way. The power of government agents to seize your electronic information at these sites – and to hold onto it for an unspecified amount of time – is virtually unlimited.

A recent court victory for the ACLU and the ACLU of Massachusetts, however, may mean the tide is turning. In House v. Napolitano, the government has been forced, as part of a settlement, to return electronic items confiscated from a man at one of these checkpoints, and to destroy all copies. The government must also turn over all files related to the investigation of the man in question, which the ACLU hopes will shed light on precisely what Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) does when it confiscates such materials.

The individual in question is David House. An activist involved in Bradley Manning Support Network, in 2010 House was involved in raising legal defense funds for the soldier accused of leaking classified documents to WikiLeaks. House’s involvement on behalf of the high profile case garnered him a place on the “Lookout” list, making it all but certain that his electronic information would be confiscated at the border. When the confiscation in fact took place upon House’s return from a trip to Mexico, his concern that government access to information about all contributors to the Manning network would discourage others from contributing propelled him to file a lawsuit, with the ACLU, claiming the government violated his First Amendment right to freedom of association and Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable search and seizure.

The individual in question is David House. An activist involved in Bradley Manning Support Network, in 2010 House was involved in raising legal defense funds for the soldier accused of leaking classified documents to WikiLeaks. House’s involvement on behalf of the high profile case garnered him a place on the “Lookout” list, making it all but certain that his electronic information would be confiscated at the border. When the confiscation in fact took place upon House’s return from a trip to Mexico, his concern that government access to information about all contributors to the Manning network would discourage others from contributing propelled him to file a lawsuit, with the ACLU, claiming the government violated his First Amendment right to freedom of association and Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable search and seizure.

A Victory Against Unlimited Electronic Border Searches

This week, the U.S. has agreed to settle the lawsuit, and has turned over the information. No doubt the ACLU will spend time wading through the investigation to uncover even more revealing information, but an initial overview has already shed light on a number of disturbing items. For instance, while the Army’s Criminal Investigation Unit, which led the investigation of Manning and looked through House’s electronic information, decided not to use any information found in House’s items against Manning, the ICE still retained copies of the documents in question. Also, the extent to which the ICE was willing to make numerous copies and share the information with a number of government agencies created the potential for House’s personal information to be easily hacked and permeated.

The settlement, along with a 2012 decision by a federal judge rejecting the federal government’s plea to dismiss the lawsuit, is a victory against an effort that has heretofore been largely hidden from the public eye. If people knew that a vacation abroad could lead to deprivation of their electronic property, and the dissemination of that property through all sorts of government agencies, it may affect what they chose to bring along for the trip. Now, the ICE is forced to limit the scope of such activity, both because precedent has been set to force turnover of confiscated information, and because the publicity of the case may mean a more educated public at the border.

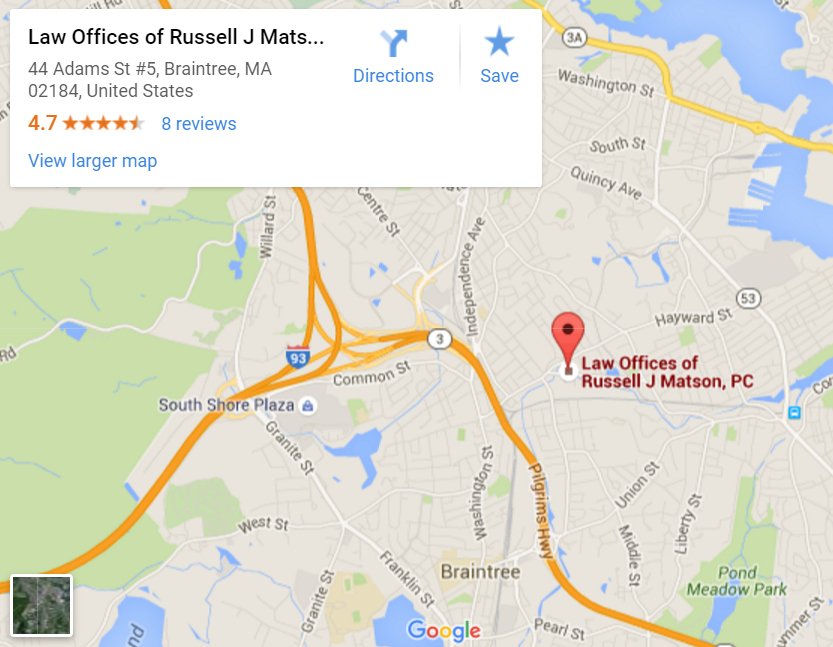

Russell Matson is a criminal and OUI defense lawyer in Massachusetts.